The Face of Another

This email has almost nothing to do with the very good Kōbō Abe novel with the same title.

Lost: Teeth, a Face // Found: The Folded Clock, another face

I’m unsure of how to introduce the most horrifying “lost thing” message I ever received other than to just quote it—

i lost my face.

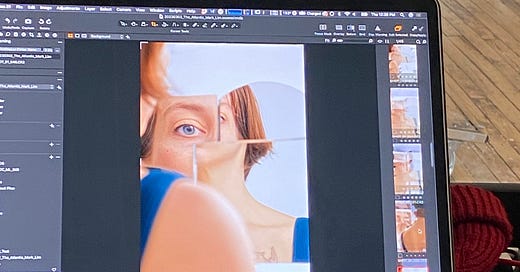

well, first I lost all my upper teeth. i had dentures for three years, awful, just bloody awful, then found some dentist to drill holes in my skull and screw a full-arch of zirconia false teeth into my face… the prosthetic “teeth” are stable, i can eat anything i want and yell “Fuck!” as loud and as forcefully as i care without a plastic plate flying out of my mouth-hole and sailing across the room onto the floor. but—these teeth he made are ugly and ill-positioned, and tiny, and too high, too far forward… it ain’t my face no more! whose fucking face IS this??

The message was signed “lulu,” the same nickname my mother uses for me. I wrote back asking what had happened to their teeth to begin with. “Bad genetics,” lulu explained, a rare problem with the roots, “no wild bar-room brawl, no horrid impa…