This is entry four into The Public Letter Project— I invited anyone who feels so moved to send me a letter, and I’ll write public replies to a few of them. Sort of like an advice column, but without direct advice. More details here.

Sterling’s letter came in shortly after I’d spent almost two weeks back in Tupelo, Mississippi, where I was born. Almost all of my family lives in four different homes in the same neighborhood where I grew up. It was the longest time I’d spent in my hometown in a very long time. Usually, I go home once a year (if that) for a three or four days; there’s barely enough time to see everyone in my family, especially since the niece and nephews require extended book-reading and hours-long games.

This time, however, I went to multiple holiday parties with my folks, caught up with old friends, talked to people whose names I didn’t immediately remember. My husband was with me, and my mother-in-law even came for a few days from Tijuana; I took them to visit Oxford to see the Faulkner House.

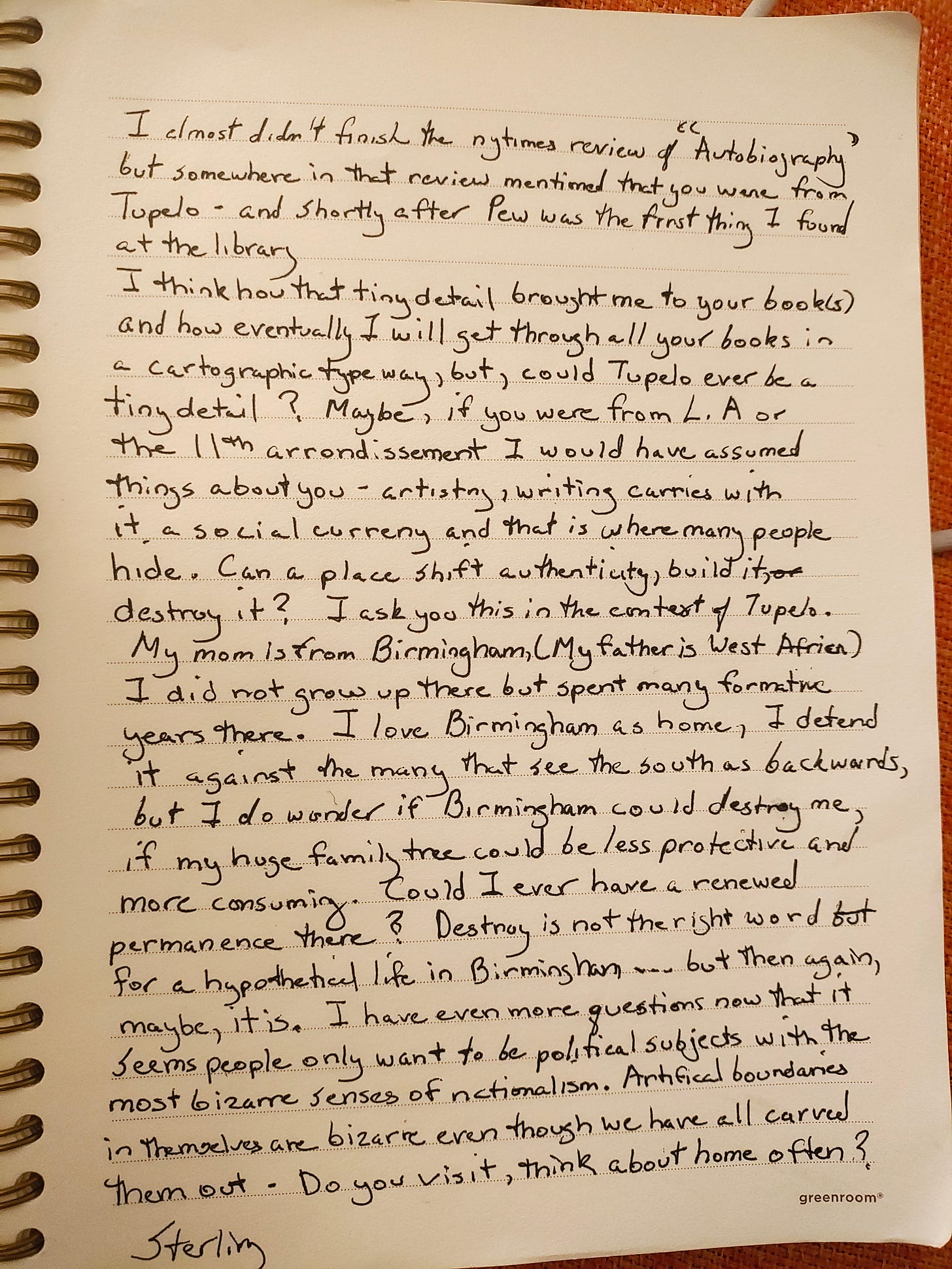

There was enough time, this year, to actually take in the place itself, not just the familiar faces, but the actual thing of Mississippi. When I got back to Mexico I felt a bit dizzied by the trip. So that’s the frame of mind I was in when I got this letter from Sterling, which is typed up below— but look how nice his handwriting is!

I almost didn’t finish the NYTimes review of [Biography of X]1 but somewhere in that review mentioned that you were from Tupelo— and shortly after Pew was the first thing I found at the library.

I think how that tiny detail brought me to your book(s) and how eventually I will get through all your books in a cartographic type way, but could Tupelo ever be a tiny detail? Maybe, if you were from LA or the 11th arrondissement I would have assumed things about you— artistry, writing carries with it a social currency and that is where many people hide. Can a place shift authenticity, build it, destroy it? I ask you this in the context of Tupelo.

My mom is from Birmingham (My father is from West Africa)

I did not grow up there but spent many formative years there. I love Birmingham as a home, I defend it against the many that see the south as backwards, but I do wonder if Birmingham could destroy me, if my huge family tree could be less protective and more consuming. Could I ever have a renewed permanence there? Destroy is not the right word for a hypothetical life in Birmingham… but then again, maybe, it is. I have even more questions now that it seems people only want to be political subjects with the most bizarre senses of nationalism. Artificial boundaries in themselves are bizarre even though we have all carved them out. Do you visit, think about home often?Sterling

Dear Sterling,

You’re right that being from Tupelo cannot be a tiny detail. But just what this detail means has always felt a bit opaque to me for various reasons.

As a kid, I thought a lot about place because I felt really out of place. Why had I been born here and not somewhere else? Why didn’t I fit in where I’d been born? Why did my hometown seem to be vaguely threatening me? There were no obvious, glaring problems in my childhood, but something felt intensely off to me. The first story I ever remember writing was a re-telling of Little Red Riding Hood, except this time a girl simply buys a red convertible and drives away. That’s all that happens. I couldn’t have been more than seven when I wrote it.

I spent a lot of time in my small town’s community theater, working on three to five plays a year. All kinds of people volunteered there, but I think it’s safe to say the closeted gays and atheists and other people who felt like outsiders were overrepresented. When there weren’t any parts for kids in a production, I volunteered to run the spotlight. This meant I had to wear all black (cool!) and got to wear a little radio headset (so cool!) through which I could listen to 30-somethings and 40-somethings cracking jokes I didn’t understand (the peak of cool.) I felt totally at home in the theater, and totally foreign the minute I stepped into the street.

At 14 (though this was extremely unusual) I left Tupelo for boarding school. My grandfather—who was born in the same house he would die in, ran the hardware store his father began, never traveled except for the war, avoided any extravagances and saved everything with a depression-era mentality— he paid for the tution. (My older brother and younger sister went too.)

I was so glad to get out of Tupelo, though the school was in Tennessee, still in the South. However, like seemingly any prep school in the States, it was aspirationally East Coast; it felt like another world. (We bragged that our campus was almost picked as the location for Dead Poets Society.) Yet there were kids there who were given Hummers for their 16th birthday, and it was the first time I saw a laptop or a cell phone, and it was the first time I met someone who wasn’t Christian. I was still bullied a lot, but I made a few friends, however temporary.

Most important to me, there was a great theater program run by a man who asked us to call him by his first name, Schaack. In my first production that fall, he cast me as “Young Prostitute” in Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Woman of Szechwan. I got to smoke real cigarettes on stage, along with the other teenagers, all of us minors, all of us smoking indoors while our parents watched. (Was it 1999 or was it 1970?) Schaack was from Tennessee, too, but he was worldly and looked like Dustin Hoffman, and had spent time in Hollywood in the 70s, or that was the lore anyway. He introduced us to Ionesco, Pinter, Albee, Brecht, and he accelerated my interest in Shakespeare. Over those four years I started to care less about acting and more about the words we were animating.

I went to college in New Orleans, which is the place that all southerners who don’t fit in the south go to be both and outsider and at home. At some point during either high school or college, I noticed that every time I went back to Tupelo, waitresses and gas station attendants would ask me where I was from; they didn’t believe me when I said I was from Tupelo. I stopped going home as often.

Decades later, when I started publishing books, I felt a confused pride when, in a big review of my fourth book, Pew, I was praised or at least given some credit for having never really played the southern card in my prior novels or stories, as if I’d been secretly southern the whole time.

But credit for what? Did the critic think I was avoiding an easy target? In fact I felt the opposite. It had never seemed like it was naturally my place to write about the South, at least not in any direct way. I knew I was a child of the South, but I never felt a part of it.

Pew is set in an abstracted version of the South, and described from the perspective of a person who doesn’t know who they are, a person who doesn’t speak, a person who looks different to everyone who looks at them— their race, gender and age are all impossible to discern. In short, an impossible person, yet this was the only kind of person I felt I could look through to see that place. The book is more a dream than a story about the south, and it remains the only way I’ve ever attempted to write directly about Mississippi. I know it comes up obliquely in other works, but it’s never been the focus again, never the main backdrop the way that it has been in my life.